305 York Lanes

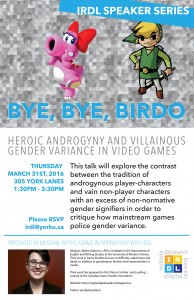

The pink dinosaur wearing a bow named “Birdo” and identified by the game manual as male in the 1988 game Super Mario Bros 2, is probably the industry’s most famous character with supposedly conflicting masculine and feminine signifiers. However, the industry is rife with characters that mix gender signifiers: what differentiates them primarily is whether this mix is portrayed as heroic androgyny or villainous gender confusion. More specifically, androgynous characters exhibit relatively few secondary sex characteristics (such as facial hair or widened hips), while gender variant characters exhibit a mix of secondary sex characteristics and social signifiers of gender (clothing, cosmetics, et cetera). This paper will explore the contrast between the tradition of androgynous player-characters like Link in The Legend of Zelda series and vain non-player characters with an excess of non-normative gender signifiers like Duvall in Resident Evil: Dead Aim. Often identified by the game as “really” male while attempting to emulate normative feminine dress and speech, these characters are presented by games as variously humorous, pitiable or monstrous. Rarely if at all can the mixing of gender signifiers be a positive, political act of genderfuck.

It would be disingenuous to identify these instances of excessive, conflicting gender signifiers without acknowledging the cultural contexts that impact Western and Eastern game production differently. Additionally, while the androgynous hero appears more commonly in game series of Japanese origin, the process by which gender variant characters are often presented by the game as transgender, even as the game discredits the legitimacy of trans and queer identity, occurs across cultural lines. However, with these acknowledgements in mind, this paper does not deconstruct transphobia in video games: instead, this chapter aims to problematize the global game industry’s acceptance of masculine-skewed androgyny as aesthetically pleasing and acceptable while portraying genderfuck as aesthetically displeasing and unacceptable. Ultimately, these differing valuations center maleness and innate masculinity as normative and present gender fluidity as inherently wrong.

This paper uses textual analysis to contrast heroic androgyny in series like The Legend of Zelda andNiGHTS with the mixing of gendered signifiers to convey the otherness of particular NPCs in games like Resident Evil: Dead Aim, Bioshock and Fable 2. Even in games that portray gender-variant characters sympathetically, such as Fire Emblem: Awakening and The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, the game takes pains to emphasize characters’ heterosexuality in order to lessen the othering effect of their gender variance.

Works Cited

Bioshock. Irrational Games, 2008. Video game.

Fire Emblem: Awakening. Nintendo SPD, 2013. Video game.

Fable 2. Lionhead Studios, 2008. Video game.

The Legend of Zelda. Nintendo R&D4, 1986. Video game.

Nights Into Dreams. Sonic Team, 1996. Video game.

Resident Evil: Dead Aim. Cavia, 2003. Video game.

Shaw, Adrienne. “The Lost Queer Potential of Fable.” Culture Digitally. 16 October 2013. Web.

Super Mario Bros. 2. Nintendo R&D4, 1988. Video game.

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. CD Projekt Red, 2015. Video game.

Meghan Blythe Adams is a PhD Candidate in the Department of English and Writing Studies at the University of Western Ontario. Their work in Game Studies focuses on difficulty, submission and death, in addition to genderqueer identity and representation in media. Their work has appeared in First Person Scholar and Loading…: Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association.

Website: http://meghanblytheadams.blogspot.ca

Twitter: @mblytheadams